|

| Winnebago |

|

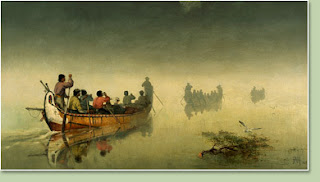

| Painting depicting Winnebago Indians at Prarie du Chien c. 1835 |

The waters flowing around the great land masses at Goose Island, La Crosse show good reason for early settlement to the area by the Winnebago Indians. The waters would provide much natural wealth and transportation, offering, later, a source for furs to trade with the French a few miles downstream at Prairie du Chien, upstream at Prarie La Crosse, and further at the Perrot trading station. We put in our kayaks at mid island and could see, as the natives would have, the rolling protective hills like great broad shoulders cradling a river which would have teemed

with life in the years previous to the fur trade to a degree that the modern traveler could hardly fathom. The first quarter of our own trip was downstream. Water trails met in between small grass islands whose tall reeds and long blades filtered the naturally muddy river nearly clean, and in places, where shallow, even clear, revealing the sandy bottom. The Winnebago would have paddled their prototype birch bark canoes, which the Voyageurs of later years would emulate. Light, agile, coasting across the surface of the water much like a crisp floating leaf, the birch bark is still considered the supreme river paddling machine of all time.

|

|

The Winnebago, like many other native tribes, although often perceived as serious and stolid, enjoyed many competitive games such as the canoe races depicted above. The men here are standing in a sprint position much in the same way we do today in order to stand-up paddle board. In 1805, the famous Zebulon Pike had been commissioned to explore the upper waters of the Mississippi and came across the first reported scene of the Winnebago playing a peculiar game, which we have come

|

| A flat prairie, much like La Crosse would have been pre-settlement |

to call

La Crosse, "Came up with prairie la crosse, so named from the ball game played on it by the Sioux. This prairie is very handsome. It is bordered by hills similar to those of the prairie des chien

... it is altogether a prospect so varied and romantic that a man may scarcely expect to enjoy such one but twice or thrice in the course of his life."

We paddled easily downstream, the current virtually dragging us, spinning us at swells if we didn't maintain good paddle rudder direction. Coming back along the banks of the backside of Goose Island, although upstream, was not as difficult as it might have been out on the main channel, where there were not as many guards against the heavy current. Turtles were the primary source of wildlife on a hot mid-afternoon, a carp jumping in the sodden weeds more towards land at hwy. 35, or the ever present red-winged blackbird screeching its trespassing call marking off its territory. At one point, though, something fabulous, as we approached quiet and slow, as if on our own version of the birch bark – up in the distance, shimmering like a badge of metal off a willow limb a small white crested bird who flit up into the air and in a loop dove down directly into the shallow water, re-emerging with

a small squiggling tadpole. The Kingfisher disappeared into the tall reeds only to reemerge at the same perch and, as wishfully predicted, did the same thing again as we silently floated underneath. As we moved deeper into the back side of the island, the boat traffic reduced to only an occasional flat-bottom buzzing through the weeds, it would be easy to imagine the hundreds of such scenes enjoyed by the native family, the wigwam erected perhaps at a clearing on the banks, the ground dug out to reveal dried dirt instead of the mosquito swarming underbrush where, when hungry, a simple

tossed line might catch dinner in an instant, just as the fishermen of today lining the campground banks hope for the same thing.